Why Audiences Flock to Faith-Based Films

March 30, 2016

David A.R. White

Producer and Star of God's Not Dead

When it comes to the box office, God is good.

David A.R. White was raised in a Mennonite household outside Dodge City, Kan., and went to the movies only one time in his first 18 years. “I was at a friend’s house, and he took me to Grease. I was 8 years old. I didn’t know what we were doing,” the 45-year-old filmmaker says, laughing. “And then Olivia Newton-John showed up in her black leather pants, and I thought for sure I was going to hell.”

In the years that followed—after playing Kurt von Trapp in a school production of The Sound of Music—White became fascinated with the entertainment industry. At 19, he moved to Los Angeles and found his niche in acting, first in the Burt Reynolds sitcomEvening Shade and eventually in independent Christian productions. In 2005 he co-founded Pure Flix Entertainment, what he calls a “Christ-centered” production-distribution company; he spent close to a decade churning out films that were popular with the Christian bookstore market but failed to score at the multiplex.

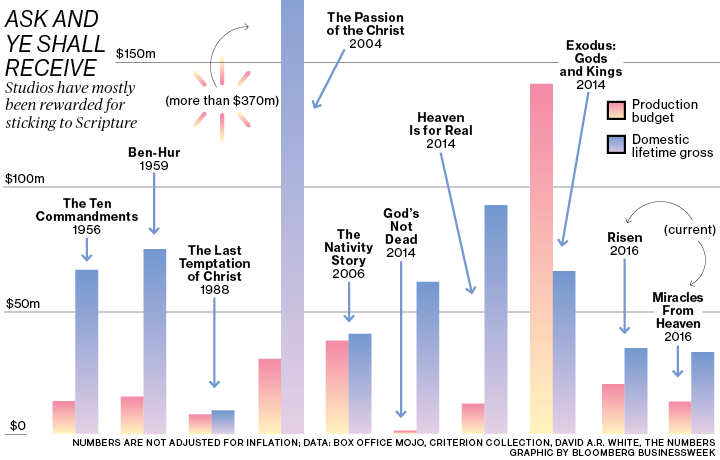

Everything changed two years ago. In 2014, White produced and starred in God’s Not Dead, an unapologetic, unsubtle Christian drama that became a word-of-mouth hit, earning $62 million against a shoestring $1.2 million budget. Today, the film—about a college student whose faith is challenged by an atheistic philosophy professor—is the fifth-most-profitable movie by percentage in cinema history, with a return on investment of 2,627 percent (positioning it, ironically, directly behind Grease).

God’s Not Dead was part of a miniwave of faith-based films that year. Now we’re seeing a flood of biblical proportions. When its sequel—God’s Not Dead 2, about a public school teacher on trial for mentioning Jesus in her classroom—hits theaters on April 1, it joins a conspicuously crowded market of Lent season releases, including Miracles From Heaven, the story of a sick child whose recovery defies medical science, and Risen, which approaches the Resurrection from the perspective of a Roman centurion.

Industry watchers assumed that Miracles and Risen would earn money slowly and steadily leading up to the Easter holiday. Instead, they surged in their opening weekends. Risen out-earned buzzy horror flick The Witch and Jesse Owens biopic Race, trailing only Marvel’s Deadpool and DreamWorks Pictures’ Kung Fu Panda 3. Miraclesrecouped its $13 million production budget in just four days, knocking the J.J. Abrams-produced 10 Cloverfield Lane out of the top three earners for the week. Explain it however you want: savvy positioning or divine intervention. But when it comes to box office returns, God is good and only getting better.

There’s nothing new about Bible films attracting rapturous audiences. After all, the movies are as old as the silver screen itself. Cecil B. DeMille’s The Ten Commandmentswas nominated for the Academy Award for Best Picture in 1956, and it’s still the sixth-highest-grossing movie of all time domestically when adjusted for inflation. “What’s different is people calling [these films] faith-based,” says director Cyrus Nowrasteh, whose film The Young Messiah, produced for an estimated $16 million and distributed by Focus Features, premiered last month. “When I was a kid, we went to see The Bibleand Ben-Hur. They were just big movies, and people went.”

Hollywood’s view of Christian films grew more agnostic in the ensuing decades. A 1977 international production of Jesus of Nazareth became a small-screen success. Martin Scorsese’s The Last Temptation of Christ (1988) was a heretical lightning rod. But for the most part, spiritual subject matters were ignored. Then in 2004, with the religious market largely relegated to the low-budget, direct-to-video format, Mel Gibson’s The Passion of the Christ banked $83 million in its opening weekend, on the way to a mammoth $611 million worldwide gross, shattering expectations of what a Christian production could earn.

“All of a sudden, everyone was interested,” says White. Some major studios cranked out a stream of high-profile commercial hits, from the allegorical (Walt Disney’s The Chronicles of Narnia, 2005) to the traditional (New Line Cinema’s The Nativity Story, 2006) to the feel-good inspirational (Warner Bros.’ The Blind Side, 2009), while others—including 20th Century Fox, the Weinstein Co., and Lionsgate—announced faith-based labels or right-of-first-refusal partnerships with Christian filmmakers. But appealing to Christian audiences turned out to be more complicated than simply making movies about Jesus. If you’ve never heard of The Ultimate Gift or The Last Sin Eater—both put out by FoxFaith, Fox’s faith-based unit—there’s a reason for that. Within a few years, most of those divisions and deals had withered and died.

“Pointing at The Passion and saying, ‘This is a great model of what faith-based films can do’ is like pointing at Star Wars and saying, ‘This is what a sci-fi movie can do.’ It’s the ultimate example of a particular genre,” says Rich Peluso, senior vice president of Sony’s Christian shingle, Affirm Films, which has fared better than most. (Affirm is behind both Miracles and Risen, as well as 2014’s Heaven Is for Real, which grossed more than $91 million in the U.S.) “But it did cause people to pay attention to the fact that the faith community will respond to a film and come out in droves.”

The most successful Christian films of the last few years have largely defied Hollywood convention. Star power takes a back seat to a loud-and-clear message. Many of the leads in God’s Not Dead and its sequel—Kevin Sorbo, Dean Cain, Melissa Joan Hart—reached peak fame in the mid-’90s. Independent producers and distributors like White’s Pure Flix have found a foothold in the space by providing supplemental study material for church groups and launching a home-streaming service in the Netflix mold. Another outfit, EchoLight Studios—whose chief executive officer is former Pennsylvania senator and onetime presidential candidate Rick Santorum—has experimented with a distribution model in which films are first released to church audiences to drum up grass-roots support.

Ultimately, conventional wide-release engagement is still the goal. “We’re looking for the same thing that Sony and Warner Bros. are looking for,” says EchoLight President Jeff Sheets. “That’s ubiquity. We want our movies to be available as soon as possible to as many people as possible.” If Tinseltown values a great story above all, how can it resist the Greatest Story Ever Told? “There’s an audience out there for these films that isn’t necessarily Christian,” The Young Messiah’s Nowrasteh says. “It’s not as if secular people can’t appreciate them.”

Chasing crossover appeal can be risky, though. Take Exodus: Gods and Kings, director Ridley Scott’s 2014 Moses-Pharaoh showdown, which went heavy on Christian Bale and light on actual Christianity and failed to recoup even half of its $140 million price tag domestically. Darren Aronofsky’s Noah, starring Russell Crowe as the Old Testament ark builder, did better at the box office the same year but drew protests from faith groups for not being true to Scripture. “Aronofsky is a self-proclaimed atheist,” White says. (Aronofsky has described himself in interviews as a humanist, not an atheist.) “The studio heads aren’t really interested in this market, nor do they really know it, so they’re thinking, We’re spending a hundred million, so let’s try to make it a crossover movie—a disaster epic. Let’s do the least amount that we have to do to gather the faith audience, because they’re stupid; they’ll come to anything that has the Bible in it. But the problem is, the faith audience isn’t stupid. They’ve been treated by Hollywood for years and years as if they are, and they’re tired of that.”

A dozen years after the post-Passion boom, Hollywood is starting to learn from the sins of the past, scaling back gluttonous budgets and vowing not to bear false witness in production and promotion. “Studios like Sony have seen that these movies are low-cost, and, if marketed correctly, they can be very profitable,” says Matthew Belloni, executive editor of the Hollywood Reporter. “It’s hit-and-miss, but the downside isn’t big. If one thing works, everyone will try to copy it.” Paramount Pictures has two faith-based films on its calendar: a remake of Ben-Hur, for which it enlisted Mark Burnett, the TV super-producer behind 2013’s most-watched miniseries, The Bible; and Same Kind of Different As Me, an inspirational love-thy-neighbor drama starring Renée Zellweger, based on a best-selling memoir that got 4.5 out of 5 stars on Christianbooks.com. In May, upstart distributor Broad Green Pictures will try its luck with Last Days in the Desert, with Ewan McGregor as Jesus and three-time Oscar winner Emmanuel Lubezki as cinematographer.

“Success begets success,” Affirm Films’ Peluso says. “As these films make a bigger impact, they start to attract other producers, directors, and talent who say, ‘Wow, this can really work.’?” White’s grateful to have the zeitgeist on his side, but he’s not depending on it. “God’s Not Dead talks a lot about religious freedoms and liberties. It’s very current to what’s happening in our society,” he says. “And it was a great story—a classic story of David overcoming Goliath. It’s our hope, certainly, that [the sequel] will go above and beyond, but we’ll serve our audience first.”

EchoLight’s big play for mainstream success will come in September, with the release ofVanished: Left Behind—Next Generation, a young-adult Rapture drama. Starring a crop of MTV talent, it invites comparisons to HBO’s The Leftovers and dystopian feature films like Divergent. While the Christian base may be more than enough to make the film a righteous profit, Sheets is banking on engagement beyond the Sunday school crowd. “One of the greatest compliments I received was from a Lionsgate executive” who saw an early cut of the film, he says. “She told me, ‘In the same way that you don’t have to believe in vampires to watch Twilight, you don’t have to be a follower of Jesus to watch Vanished.’ She’s exactly right.”

Source: David Walters via Bloomberg.com